Understanding the impact of increased cost of living on gambling behaviour: Gambling Commission’s interim findings

Last month, the Gambling Commission published its interim findings on the impact of increased cost of living on gambling behaviour. The Gambling Commission’s research aims to improve its understanding of the impact of increased cost of living by examining the behaviours and motivations of gamblers during the period of high cost of living in Great Britain (“COL Research”).

The Gambling Commission commenced the COL Research in December 2022 in partnership with Yonder Consulting, and undertook a “mixed-methodology research approach” with a longitudinal survey taking place over three waves between December 2022 and June 2023. This was followed by qualitative depth interviews to further understand the impact of the rise in cost of living on lifestyle and gambling behaviours.

In this blog, we summarise the COL Research, set out the Gambling Commission’s interim findings and identify key points for licensees in Great Britain to note.

What is the COL Research?

The Gambling Commission sets out its definition of ‘cost of living’, as:

“the amount of money that is needed to cover basic expenses such as housing, food, taxes, healthcare, and a certain standard of living.”

The COL Research specifically aims to test three core hypotheses:

- The rise in cost of living is likely to impact consumers’ gambling behaviour in different ways, depending on their personal circumstances and the way in which gambling fits into their lives.

- Some gamblers will report that the rise in cost of living has had a mediating effect on their gambling behaviour.

- The rise in cost of living may negatively impact vulnerabilities for some consumers, putting them at an increased risk of gambling-related harm.

The project commenced with three waves of quantitative research, which sought to: (1) initially establish a baseline of key gambling behaviours; (2) explore the impact of external triggers for gambling; and (3) subsequently track any changes to the core gambling behaviours.

Wave 1

Between 21 and 22 December 2022 the Gambling Commission commenced the nationally representative survey of 2,065 adults aged 18 or over. 973 participants (47%) had engaged in gambling activity in the last four weeks.

Wave 2

Between 27 February and 3 March 2023, 1,694 of the same sample group were recontacted to capture changes in the core gambling behaviours surveyed. 820 participants (48%) had engaged in gambling activity in the last four weeks.

Wave 3

Between 26 May and 2 June 2023, 1,391 of the same sample group (who all took part in Wave 2) were recontacted to capture further changes in the core gambling behaviours. 666 participants (48%) had engaged in gambling activity in the last four weeks.

Qualitative wave

The qualitative phase took place in August 2023, with the aim to build a “more rounded impression and picture of each individual”. This phase engaged with 16 individuals who each completed a three-day “digital diary pre-task” to reflect on spending habits. 16 one-hour online interviews were then conducted with gamblers who engage in a variety of different gambling types and with different gambling behaviours (whilst it is not clear, we assume these were the same 16 individuals who participated in the digital diary pre-task).

The Gambling Commission’s interim report does not discuss findings from the qualitative phase; these will accompany further quantitative and longitudinal analyses in the final report expected in “early 2024”.

Key findings

The quantitative phase of the COL Research (i.e. the three waves) surveyed the participants across three broad topics. We set out the Gambling Commission’s key findings for each topic below.

Topic 1: Financial comfort and concerns, and wellbeing

- Just under half of the respondents indicated they were “just about managing but felt confident that they would be okay” with the cost of living, whereas between 40% and 43% of individuals indicated they were “financially comfortable”.

- The subgroups most likely to have broader concerns about their personal finances are those who gamble online and those who score 8 or more on the Problem Gambling Severity Index (“PGSI”), however most individuals signalled the need to take steps to make their income go further during the tracked period.

- In terms of wellbeing, between 45% and 49% of respondents reported “not being able to enjoy the things that they used to due to the rising cost of living” throughout the tracked period.

Topic 2: Changes in gambling behaviours

- Despite the rise in cost of living, a clear majority of gamblers reported that their gambling behaviours (amount of time and money spent, number of gambling occasions and typical stake placed) had remained stable, the majority ranging from 62% to 75% depending on the type of gambling behaviour.

- If a change in gambling behaviour was reported, it was much more likely to be a decrease in gambling. For example, between 22% and 26% of individuals reported a decrease in the amount of time spent gambling, compared to 6% to 7% that reported an increase in time spent gambling.

- 69% of individuals who did report changes indicated that these changes were “at least partially a direct consequence” of increases in the cost of living.

- Individuals who scored 8 or more on the PGSI were more likely to report an increase in the gambling behaviours surveyed, despite the rise in cost of living.

Topic 3: Motivations for gambling

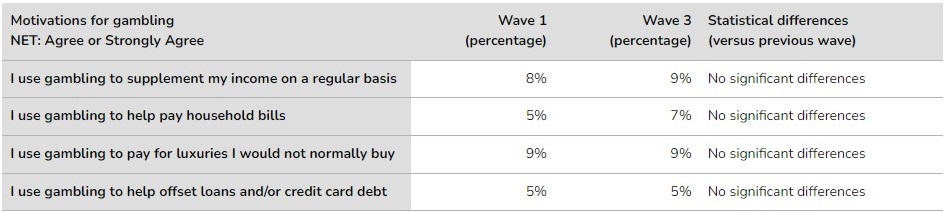

- Respondents who previously indicated they had changed their gambling behaviours were asked questions about four specific motivations in Waves 1 and 3, displayed in the Gambling Commission’s Table 4.1:

- Between 10% and 20% of online gamblers indicated that bolstering their finances was their motivation for gambling, and this motivation applied to “significantly more” individuals who scored 8 or more on the PGSI.

Interim conclusions

The concluding remarks in the Gambling Commission’s report considered the interim findings in the context of the following two hypotheses:

Has the rise in cost of living had a mediating effect on gambling behaviour?

Initial quantitative evidence does not suggest that the rise in cost of living has had a mediating effect on gambling behaviours. However, the “small proportion” of those who did make changes to their gambling during this period were more likely to have deceased their gambling; the exception being individuals who scored 8 or higher on the PGSI, who were more likely to have increased their gambling compared to other groups of participants.

Has the rise in cost of living negatively impacted vulnerabilities for some consumers?

A small minority of gamblers who said that they have changed at least one of the surveyed gambling behaviours reported using gambling to support their finances in some way, with a greater proportion of those doing so being online gamblers and/or those who scored 8 or more on the PGSI. The individuals who did change their gambling behaviours indicated that the rise of cost of living has at least partially contributed to their change in behaviour.

Takeaway points

It can be inferred from the interim findings that online gamblers and individuals scoring 8 or higher on the PGSI may be more vulnerable to gambling-related harms when faced with a rise in cost of living.

Given that the interim findings come at a time when the spotlight is on affordability and customer interaction, it will be interesting to see whether the COL Research findings feature prominently in the Gambling Commission’s response to its summer consultation that closed on 18 October 2023 and included consideration of new obligations on licensees to conduct financial vulnerability checks and financial risk assessments.

For the meantime, online operators in particular, should bear these interim findings in mind while they are updating their safer gambling policies and procedures to reflect the Gambling Commission’s revised customer interaction guidance for remote gambling licensees; and evaluate whether they ought to take increased cost of living into account in their assessment of financial risk – pending formal direction from the Gambling Commission.

The Gambling Commission’s final report in “early 2024” will combine its interim findings with further quantitative analysis of the longitudinal impact of the increased cost of living across different demographic groups, and key findings from its qualitative phase of the COL Research.

Please get in contact with us if you have any questions about the Gambling Commission’s interim findings and/or your business’ approach to customer interaction and financial vulnerability.