White Paper Series: Give your two pounds’ worth on DCMS’ consultation for online slots stake limits

The consultation season well and truly began on 26 July 2023, with the Department for Culture, Media and Sport (“DCMS”) publishing the first two of its promised consultations from the White Paper. In this latest edition of our White Paper Series, we discuss DCMS’ proposals and reasoning for a maximum stake limit for online slots games in Great Britain (the “Slots Consultation”) and strongly encourage the industry to respond.

1. Background

As discussed in our previous White Paper Series blog on stake limits, DCMS foreshadowed its reasons for the Slots Consultation in the White Paper.

It noted that slots have the highest average losses per active customer of any online gambling product, the highest number of players, the longest play sessions and the greatest potential for financial harm, due to the velocity at which people can stake, with no statutory limit on the amount they can stake. On the other hand, it was acknowledged that online operators are uniquely able to regularly monitor and scrutinise their customers’ spending on slots and intervene where necessary.

In the end, having considered the evidence available to it, DCMS concluded that reform was necessary. Although evidence of a clear causative relationship was limited, there was sufficient evidence of an association between higher stakes on online slots and identified risks of harm. DCMS determined it was time for change: there would be a consultation in summer 2023 on a stake limit for online slots of between £2 and £15. In addition, DCMS would also consult on a preferred £2 limit for those aged 18 to 24.

2. The proposals – General population

The Slots Consultation has now been published and DCMS has proposed four options for the maximum stake limit which should apply for online slots, seeking opinions on which option “strikes an appropriate balance between preventing harm and preserving consumer freedoms”.

We discuss the options and DCMS’ headline reasoning for each stake limit below:

Option 1 – A maximum online slots stake limit of £2 per spin

The industry knew £2 stake limits were going to be the starting point for the Slots Consultation and unsurprisingly, this option would have the greatest impact on consumers and businesses alike. DCMS recognises that 97% of all individual online slot stakes are below £2. However, up to 35% of players stake over £2 on a single spin at least once a year. Of course, £2 is a relatively low bar especially given that stakes over this threshold contribute to an estimated 18% of annual slots gross gambling yield (“GGY”). Option 1 would therefore have a significant impact on online casino operators and the industry’s GGY broadly.

Option 2 – A maximum online slots stake limit of £5 per spin

A £5 maximum stake per spin, as DCMS notes, is equal to the highest limit currently permitted on any land-based gaming machine.

There may be a superficial attraction to aligning online slots with the limits imposed on their land-based counterparts, but it would not come without a significant impact to the online industry which already has a wider system of safer gambling protections in place. Indeed, DCMS acknowledges this in the White Paper:

“The stake limits already applied to electronic gaming machines in the land-based sector could be a sensible starting point. However, taking an equitable approach to product regulation should take account of the wider system of protections in place online. For instance, the opportunity for data-driven monitoring of online play may justify a higher limit for online products than in relatively anonymous land-based settings.”

DCMS estimates stakes over £5 represent only 0.5% of online slots staking events but represent approximately 7.4% of slots GGY.

Option 3 – A maximum online slots stake limit of £10 per spin

Although a £10 maximum stake per spin is higher than any stakes permitted on a land-based gaming machine, DCMS is considering whether these higher limits are appropriate in the online world given that there are additional protections for online players, who are required to create an account to play and can therefore be more adequately monitored by licensed operators for signs of gambling-related harm (as suggested in the above quote).

This is particularly relevant given that DCMS does not anticipate severe disruptions to the majority of slots players if Option 3 is implemented, noting that 37% of all stakes placed above £10 were made by high and medium risk players.

As we hinted in our previous blog, it is possible DCMS will be drawn to setting £5 (Option 2) as the maximum stake limit for online slots, noting this figure appeared in an earlier leaked version of the White Paper. However, given its acknowledgement in the above quote, we believe DCMS is open to considering evidence-based responses which favour a higher limit. This is of course dependent on the industry submitting compelling evidence-based responses to the Slots Consultation.

Option 4 – A maximum online slots stake limit of £15 per spin

As with Option 1, the industry was aware a £15 stake limit would represent the maximum stake per spin in the Slots Consultation. Broadly, DCMS considers this stake limit would impact only a small minority of “habitually or occasionally high-staking players”, where stakes over £15 represent 0.05% of all stakes on online slots and 2% of GGY. We consider it unlikely that Option 4 is the option that will finally be adopted.

3. The proposals – 18 to 24 year olds

As we previously discussed, the White Paper committed to consulting on additional protections for young adults aged between 18 to 24 years on the basis that this age group may be a “particularly vulnerable cohort”.

The Slots Consultation cites the Gambling Commission’s Advice to Government for the Review of the Gambling Act 2005 in identifying a number of potential factors influencing gambling behaviours in young adulthood, including continuing cognitive development, changing support networks and inexperience with money management. DCMS separately noted that problem gambling rates are highest in the 16 to 24 years age group, according to the Public Health England and Gambling-related harms evidence review of 2019.

Accordingly, the Slots Consultation seeks views on the following three options:

- Option A – A maximum online slots stake limit of £2 per spin for 18 to 24 year olds

- Option B – A maximum online slots stake limit of £4 per spin for 18 to 24 year olds

- Option C – Applying the same maximum stake limit to all adults, but building wider requirements for operators to consider age as a risk factor for gambling-related harm.

In setting out its evidence, DCMS acknowledges that typical online slots stakes for those aged 18 to 24 are lower than for other adult age groups. Data captured between July 2018 to June 2019 indicates the mean stake in this cohort was £1.05 compared to £1.30 across all adults aged 25 and over, and DCMS cites data indicating the age group’s average stake is 20% lower than the average for all adults (according to Patterns of Play).

In respect of the specific limits proposed in Options A and B, DCMS does not cite data that specifically indicates either maximum stake limit would be best suited to this age group. The reasoning simply appears to be that as a potentially vulnerable cohort, there should be extra protections in place, i.e. lower maximum stake limits than those for the general population.

Option C would of course be the least intrusive option for operators and their customers, and any action required of operators would likely align with the Gambling Commission’s consultation on, and likely increase to, the requirements for operators to check customers’ individual financial circumstances in respect of indicators that their losses are harmful. Watch out for more on this in a forthcoming White Paper Series blog.

4. DCMS data and considerations

The status quo

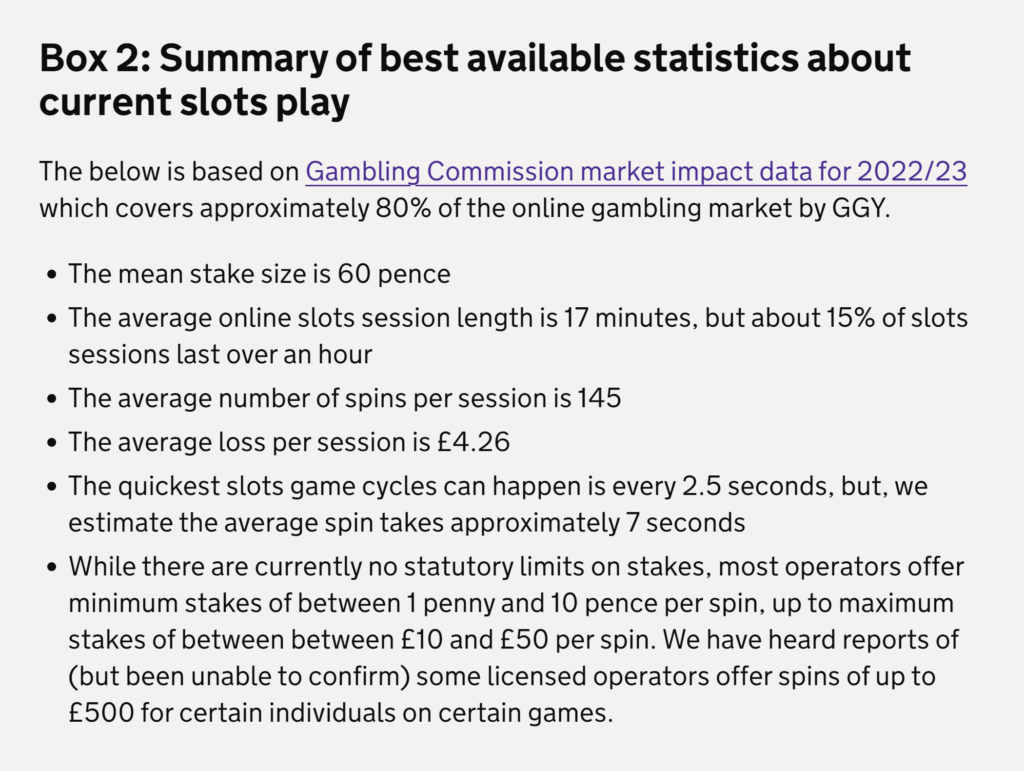

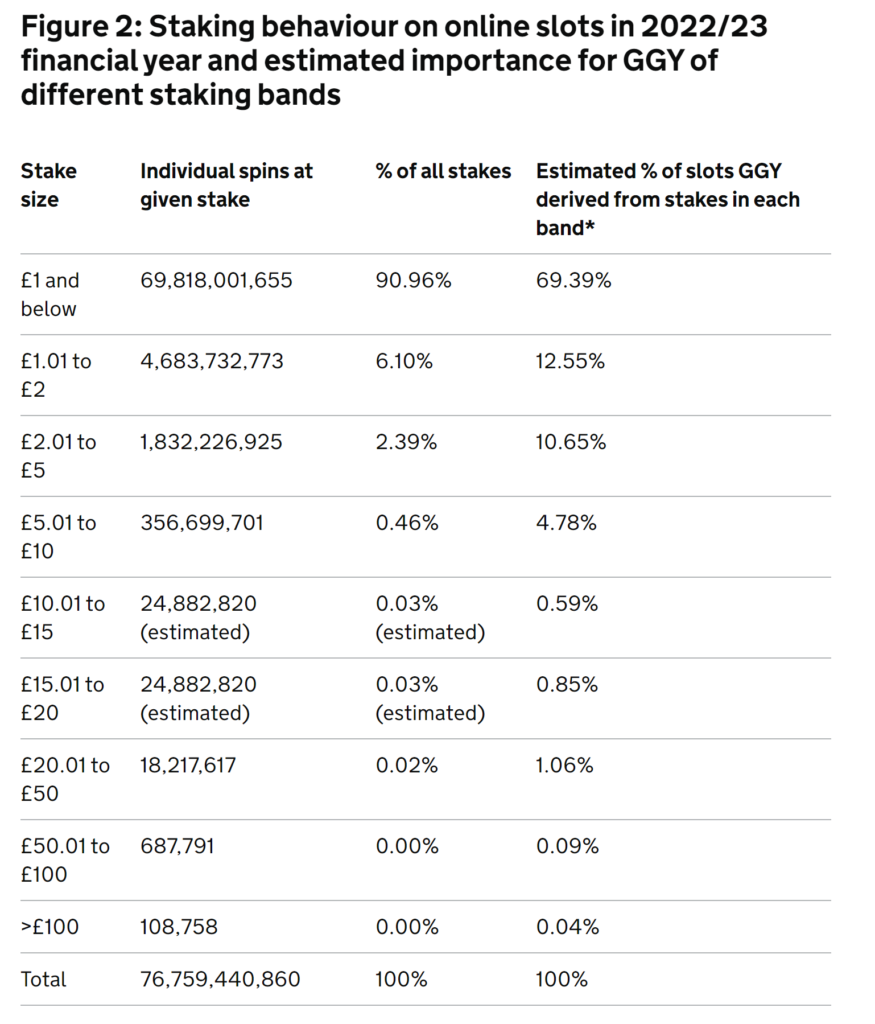

In the Slots Consultation, DCMS cites Gambling Commission data in summarising the best available statistics about current slots play, set out below:

Furthermore, DCMS sets out staking behaviour for the 2022/23 financial year (representing more than 76 billion spins) which it uses to underpin its consideration of the likely impact of each maximum stake limit:

(The estimated % of slots GGY in Figure 2 assumes that all slots games have a 95% return to player and the distribution of spend within each bucket is modelled as non-linear.)

Aside from the sheer scale of online slots activity in the last financial year, the data presented in the Slots Consultation (including that shown in the above two figures) breathes life into DCMS’ proposals which, if we return to first principles, have been drafted in order to address the fact that there is evidence of a relationship between higher staking on slots and gambling-related harm.

By removing the ability for an arguably very small proportion of slots players to stake high(er) amounts on slots, will this aim be achieved? From the above data, we can see that most online slots spins from the last financial year would not be impacted by any of the proposed stake limits. However, the changes would result in a significant reduction in the industry’s GGY (we discuss this in further detail below).

Potential impact

So, has an appropriate balance been struck? Whilst we do not think there is a straightforward answer to this question (hence DCMS releasing the Slots Consultation), the potential impact of each of the options considered are set out in DCMS’ Online Slots Stake Limit Impact Assessment (the “Impact Assessment”), published alongside the Slots Consultation.

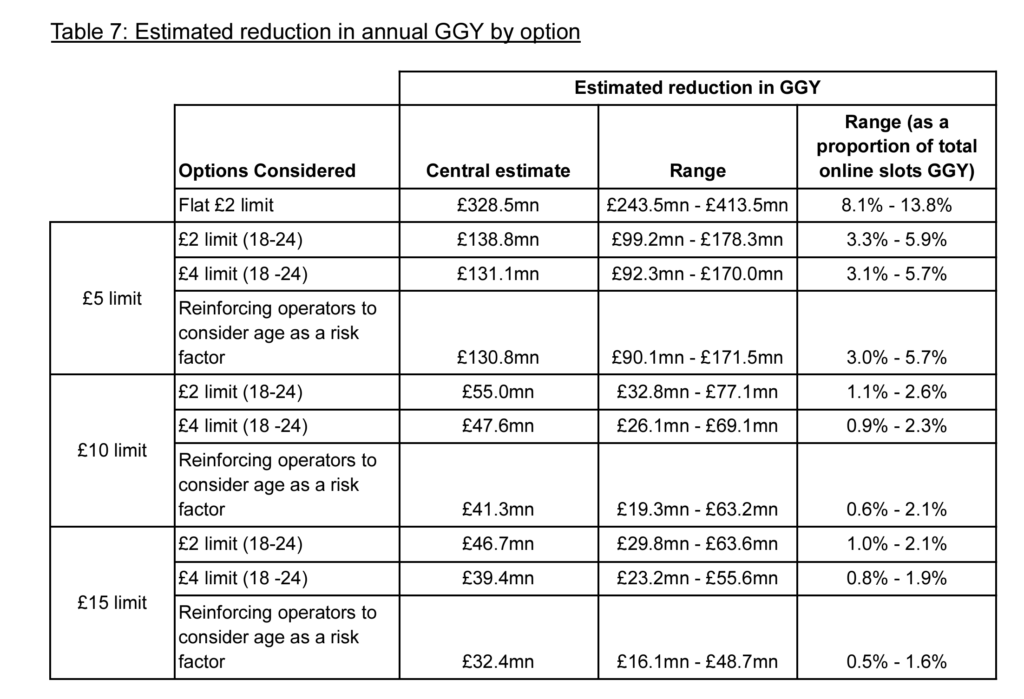

Interestingly, the Impact Assessment models the estimated reduction in annual GGY in the industry for each option considered in Slots Consultation, as follows:

To summarise this data, the Impact Assessment suggests that there will be an estimated reduction in the current annual online slots GGY of between 0.5% to 13.8%, ranging in real terms, from a £16.1m to £413.5m reduction in revenue annually.

Aside from the costs to business, the Impact Assessment also sets out the potential benefits of the maximum stake limits and shares the associated assumptions that DCMS made in coming to these conclusions. It is particularly worth noting that DCMS acknowledges it is difficult to accurately estimate gambling harm reduction from stake limits, stating:

“Gambling harm is complex and often the result of numerous factors both within and external to the actual gambling environment. It would be difficult to isolate the causal mechanism between staking at various levels (that will no longer be available) and the reduction in gambling harm.”

However, it goes on to note that there are clear, qualitative benefits to the stake limits for both the customer and the public sector. To pick a crucial example, the Impact Assessment identifies that each stake limit will have an impact on a customer’s risk of incurring runaway losses, and suffering gambling harm as a result of these losses.

Additionally, public sector benefits would include potential reductions in costs incurred by the public sector in respect of harmful gambling costs which include:

a) Primary care mental health services, secondary mental health services, and hospital inpatient services;

b) Job seekers allowance claimant costs and lost labour tax receipts;

c) Statutory homelessness applications; and

d) Incarceration costs.

We encourage all licensees and stakeholders to review the Impact Assessment, in addition to the Slots Consultation, for a closer look at the estimated costs and benefits of the proposed stake limits and to better inform views on where the balance between protection from harm and consumer freedom lies.

5. Responding to the Slots Consultation

The Slots Consultation will be open for responses for eight weeks only, until 11:55pm on 20 September 2023. Responses can be submitted through DCMS’ online survey, or as a Word or PDF document to [email protected]. DCMS is encouraging evidence from all parties who have an interest in the way gambling is regulated in Great Britain, including any international evidence.

Following the consultation period, DCMS will publish a formal response setting out its decisions in relation to the maximum stake limit proposals and its reasoning, as well as a final impact assessment, before implementing the changes. Changes will likely be made by way of the introduction of secondary legislation, e.g. the creation of a new licence condition for Gambling Commission licensees.

In the short time before the Slots Consultation closes, we strongly encourage all licensees and other stakeholders to consider the impact the proposals would have on their businesses and respond with evidence-based submissions. Now is the opportunity to influence positive change for consumer protection whilst tempering a potentially damaging blow to the commercial viability of the online slots industry in Great Britain.

Please get in touch with us if you would like assistance with preparing a response to this or any other DCMS and Gambling Commission consultations.

With thanks to Gemma Boore for her invaluable co-authorship.